Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

by Dr Jim Walsh, CEO of Conway Hall

Yes. But not for the reasons you might suspect.

There are, of course, green considerations to be made regarding travel, food consumption and a whole host of decisions regarding personal hygiene measures and single-use plastics. These are indeed ethical issues. However, I want to discuss a different kind of ethics in relation to festivals.

Let me start with a personal memory. When I used to go to gigs as a teenager with my friends, we saw hundreds of bands in the course a seemingly never-ending stream of Friday and Saturday nights, driving to different venues in the hope of seeing a “great band”. Often, we were disappointed. Mainly, I reflect with the benefit of hindsight, because we were musical snobs. However, on occasion we would see a “good band” and they might have even been “great” – but one of my mates would say something in my ear like “their bassist is crap” or “not this bloody cover again”. Sometimes, I’ll admit, even I would say something similar. But if I was enjoying the gig/band/song, any such comment would act like a drink being thrown in my face. Although at the time I would yield to my friend’s camaraderie and snicker with them, later this memory of the night would not sit well, and I never knew why.

The issue rests on the pivot-point of: how much do we want to lose ourselves in the experience? Do we want to be ‘lost in music’ or do we want to always maintain self-awareness and self-control?

The issue rests on the pivot-point of: how much do we want to lose ourselves in the experience? Do we want to be ‘lost in music’ or do we want to always maintain self-awareness and self-control?

Surely, the point of the festival is that we allow ourselves some space for the extra-ordinary in our lives. If this is true, then bringing the ordinary – self-awareness and self-control – along isn’t really going to get us very far. The argument being that we need to enable a certain forgetting of ourselves and our usual pre-occupations.

Bringing cynicism, interpretation, and a lack of openness to a gig or a festival will certainly dampen down the extra-ordinary – as my adolescent self can testify. The whisper of “Gawd, look at those trousers” really brings reality crashing back if the atmosphere had just started to quicken and gather pace.

The lesson, of course, is that cynics, witty commentators, and killjoys rarely leave the comfort of their own misanthropy and internal musings to experience real life. Life’s rich pageant is purely something to be witnessed from behind their reinforced-glass observation pane. To live, one must slip from their side and dare to cut the mooring ropes that bind us to the misery of cynical existence and drift into the wonderment of engaging, participating and living. It won’t always be pleasant, but it will be authentic. So, relax, get carried away and enjoy something real rather than projecting the same old same old. There are amazing, beautiful, life-enhancing experiences to be had at gigs and festivals as long as you and your mates leave your normal everyday selves at home.

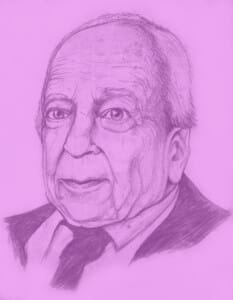

The next ethical point about festivals is best summed up by Hans-Georg Gadamer, a philosopher who lived to be 102! So, you might argue he would know a thing or two about how to live.

The particular point Gadamer makes about festivals is that a certain space is created where we are bound together in an experience of community. And, for Gadamer, this experience is the most perfect form of community. The basis for his elevation of this form of community is that we feel the connection rather than think about the connection to others. Entwined within this way of feeling connected to others, Gadamer recognises the same importance of self-forgetting that we saw previously. To help us understand this let’s look at an example and at the same time broaden our thoughts as to what might constitute a ‘festival’.

At Conway Hall we have been programming a series of chamber music concerts on Sundays since 1887. From a Gadamerian perspective, these concerts enable a community. When the Schwarzenberg Trio are in mid-flow of Haydn’s Trio in C Op.86/1 the audience are present and engaged watching and listening. They are giving their entire focus to the performers. No conversation, whispering, or comments are made, just watching and listening. This makes the experience for the audience one that places their self to one side in preference for the visual and aural stimuli their receive from the stage (the first ethical point we discussed).

However, because the audience is not made up of just one person but hundreds the experience becomes shared and a community at that moment exists. Each member of the audience undergoes the same experience (subject to physical differences in seat location and the varying individual ranges of seeing and hearing).

Those audience members truly share a unique experience together. What they experience can’t be given to a friend, colleague or family member after the fact because that person wasn’t there at that time. It is only by being present that the experience happens, and it is only for those few hundred people.

Consequently, therefore, the event has a select community who undergo the experience together. Afterwards they might well converse with each other to share their thoughts and feelings verbally. However, during the performance, when their selves and thoughts are placed to one side, as well as watching and listening a feeling of connection to those fellow audience members develops because they are all sharing the same experience – in this case the beauty of chamber music played at its best.

As one who has been to a few concerts, and possibly more gigs, I know this feeling well and sincerely hope that you do too because there is a uniting bond – an ethics – right there in that community feeling.

The issue rests on the pivot-point of: how much do we want to lose ourselves in the experience? Do we want to be ‘lost in music’ or do we want to always maintain self-awareness and self-control?

The issue rests on the pivot-point of: how much do we want to lose ourselves in the experience? Do we want to be ‘lost in music’ or do we want to always maintain self-awareness and self-control?