Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

In her time living in Dalston, London, immersed in the beauty of the outdoors, Victorian composer Eliza Flower reflected on her submersion in nature as akin to being in a songbird’s cage, but open; her garden regarded as a “bucolic, romantic retreat“. Beyond her love for nature, this period in her life, and her compositions inspired by it, were notably emblematic of her unsung significance in the secularisation of the hymn, of an emergence of free liberal thought and discussion driven by women in the late 19th century.

Today, it may be surprising to think of the hymn as a medium for protest, with its religious connotations of calls to prayer, but its fundamental meaning is one deserving of contestation. Much like a song of protest, the hymn demonstrates an appeal to a higher cause beyond the self, making it a fitting medium for political calls to action. Of course, we’ve seen this with the likes of suffragette composers like Ethel Smyth, Theodora Mills and Alicia Needham in compositions and works we come to understand today as feminist protest songs, which articulated the insurgence of the Suffragette movement into musical form. What often goes amiss, however, is the influence of the secularisation of traditional religious ballads on these compositions.

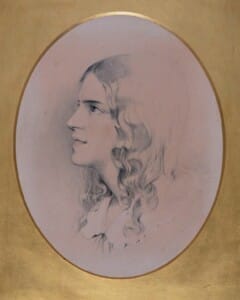

A self-taught composer born in Harlow, Essex in 1803, to political writer, printer and radical father Benjamin Flower, and sister to poet Sarah Flower Adams, Eliza Flower regularly composed and produced hymns for the South Place Unitarian Chapel’s Sunday services. Often in collaboration with writer and theorist Harriet Martineau (who once made the observation of Flower, “Everything suggested music to her”) Flower enjoyed a partnership for a number of songs: Martineau often would compose lyrics which Flower would arrange to accompany unconventional and intricate musical compositions – many of which were politically inclined in nature. Flower’s eccentricity notably extended to her personal life, where her move to live with political reformer William J. Fox, recently separated from his wife, was seen as highly unusual at the time and became a point of contention between Flower and Martineau.

A self-taught composer born in Harlow, Essex in 1803, to political writer, printer and radical father Benjamin Flower, and sister to poet Sarah Flower Adams, Eliza Flower regularly composed and produced hymns for the South Place Unitarian Chapel’s Sunday services. Often in collaboration with writer and theorist Harriet Martineau (who once made the observation of Flower, “Everything suggested music to her”) Flower enjoyed a partnership for a number of songs: Martineau often would compose lyrics which Flower would arrange to accompany unconventional and intricate musical compositions – many of which were politically inclined in nature. Flower’s eccentricity notably extended to her personal life, where her move to live with political reformer William J. Fox, recently separated from his wife, was seen as highly unusual at the time and became a point of contention between Flower and Martineau.

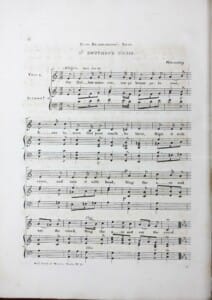

Flower’s compositions continued to be produced in the Theological Monthly Repository (later renamed the Monthly Repository to reflect the periodical’s change in content direction) and would have been major selling points within the repository for the middle–classes. Flower’s songs arguably played an important role in secularising congregations and religious institutions. Her produced works became a part of the official repertoire of the South Place Society, a non-conformist organisation preoccupied with new radicalism and deconstructing the bounds of liturgical worship. Fox’s appointment as the minister of the society in 1817 was met with protest due to the repertoire’s “incompatibility” with piousness and an inability to invoke the Divine in its congregation. So lies this article’s fascination with the hymn and the protest song’s inherent interrelations. The protest song notably functions as a declaration for radical action, made to empower the overcoming of adversity, evoke the action of a social movement and initiate the challenging of structural powers.

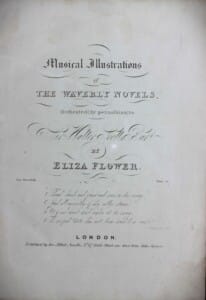

Flower’s works devolved from an interest in reconciling through music both the sacred and the unspiritual. Free Trade Songs of the Seasons (1845), written and composed with her sister Sarah for a bazaar at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, were composed with the intention of being sold to and sung by women to their husbands, sons and brothers as a call to action and a means to spread significant messages relating to politics, poverty, and societal change at large through the medium of song.

Much like the hymn’s inherent aim to bring an individual to a point of faith and allude to a greater cause, Flower’s compositions arguably sought to establish the sentiment of collective identification clearly relevant to the nineteenth-century working classes in their calls for liberation and political agency.

Her songs of a more politically explicit nature, including The Barons Bold, on Runnymede (1832) and The Gathering of the Unions (1832), demonstrated more radical yet nonviolent calls to action with lyrics of a radical persuasion yet epitomising that of self-actualisation and spirituality as seen in traditional hymns. Utilising then modern musical approaches, Flower’s compositions demonstrated a strain between the divine and the profane, arguably to the benefit of individual and collective transcendentalism. Her works, then coinciding with the era of the gathering of the unions towards the mid-19th century, evidently ring relevant today, with continual strikes and calls for fairer pay a situation all too familiar for many amid the ongoing cost-of-living crisis.

Following her death in 1846 and Fox’s departure from his ministerial role at South Place, Flower’s impact would continue to resonate in its congregation; hymns of a more religious and sacred nature would be performed by its choir, whereas the general congregation would perform secular compositions of a humanist nature. The secularisation of South Place continued right into the late 19th century culminating in its eventual name change in 1888 to South Place Ethical Society, where preaching was less commonplace and ‘lectures’ became the norm, punctuated by Flower’s hymns which were recontextualised from their original devotional and spiritual intent.

Flower’s legacy was sustained even into the 20th century; protest songs of a more profane nature were much more commonplace and indebted to the hymn’s emergent secularisation and socialistic thought. This is seen in the works of the suffragettes, utilised in contexts (such as military marches) where religiosity was evident, but songs of a much less reverential nature were performed. Instead, as music historian Oskar Jensen has argued, what Flower’s songs proposed were that these compositions were essentially divine in and of themselves, despite their secularisation, propelling appeals to action and the inner strength of the self. To all appearances, this sentiment mirrors the South Place Ethical Society’s ideological evolvement to what we now know today as Conway Hall.

As a modern-day ethical society, where can reattaining this heritage through the means of archiving get us? Just as the mobilisation of protest and calls to action in music are an ever-evolving conception, so too is the preservation of its past forms and our understandings of the ways in which its meanings are created. Conway Hall’s archives are currently home to several of Flower’s manuscripts, and we will be collaborating in a partnership with Electric Voice Theatre and Oskar Jensen this October for an evening celebrating her life and compositions in the context of her contemporaries, Franz Schubert and Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel.

As a modern-day ethical society, where can reattaining this heritage through the means of archiving get us? Just as the mobilisation of protest and calls to action in music are an ever-evolving conception, so too is the preservation of its past forms and our understandings of the ways in which its meanings are created. Conway Hall’s archives are currently home to several of Flower’s manuscripts, and we will be collaborating in a partnership with Electric Voice Theatre and Oskar Jensen this October for an evening celebrating her life and compositions in the context of her contemporaries, Franz Schubert and Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel.

The advantage of Conway Hall as both a conservation haven for freethinkers, radicals and reformers and an ever-growing research collection is its power to document connections between its complex history and the community in reflecting on societal issues, similarly encountered in Flower’s songs. Today, Conway Hall’s Library is well suited to conserve these connections, and furthermore, engage with new means of archiving radical action in an increasingly digital era.

As the protest song has evolved over the years into its varying diminutives, an increasingly secularised society has resulted in the diminishment of the hymn as a musical form of protest. Flower’s works remain prevalent in our understandings of how tensions between the secular and the spiritual have come to predominate radical struggle in society since her death. Perhaps there really is merit to the idea that “protest hymns” are a thing of the past. Archiving and ultimately reviving Flower’s songs through performance today notably emblematises the development of the community-based archive as a concept, in which preserving Flower’s story and her repurposing of the hymn is a form of activism in its own right.

Join Electric Voice Theatre and Oskar Jensen for an evening at Conway Hall for Flowers of the Seasons: Politics, Power and Poverty on Friday 27 October 2023. Tickets can be purchased here: Conway Hall | Flowers of the Seasons: Politics, Power & Poverty