Estimated reading time: 2 minutes

This blog comes from our volunteer, Cami Garcia, who selected Austin Holyoake’s neo-Malthusian pamphlet ‘Large or small families? On which side lies the balance of comfort?’ as a highlight of our nineteenth-century pamphlet collection. Austin Holyoake, brother of secularist and co-operator George Jacob Holyoake, was a radical printer and publisher and campaigner for secularism and freethought. This pamphlet is just one of over 1300 nineteenth-century pamphlets we are making freely available online through the National Lottery Heritage Funded digitisation project Victorian Blogging.

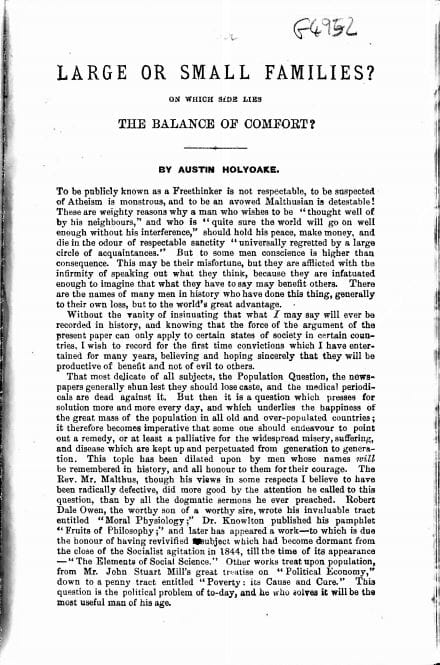

The first page of the pamphlet, available to view in full on our digital collections page.

Austin Holyoake, whose conscience may be said to be higher than consequence, pressed for solutions to the Population Question to secure the happiness of the great mass of the population in all old and over-populated countries.

In his pamphlet Large or small families? On which side lies the balance of comfort? he declares the various schemes for the amelioration of the growing want and misery of this country, such as home colonisation, emigration, co-operation, and trades’ unions.

Austin observed a correlation between an increasing population and increasing poverty, pauperism, and starvation, whilst arguing that human life shares the fate of every other ‘article’ which gluts the market: it becomes depreciated in value so long as the supply is abundant. England, after all, he declares, is a small country and, in proportion to the land under cultivation for food, it is over-populated.

He goes on to say that migration schemes, which would sever the ties of kindred and home, cannot be the answer. Yet, Holyoake mentions that those who seek subsistence in the uncultivated wilds of a foreign land thousands of miles away are different to the ‘roving Englishman’ who is generally a person of means who travels about the world for his own amusement, knowing he can return at any moment he feels home sick.

Thus, a working man in London and not the ‘roving Englishman’ is set to become like ‘Harry Despond, who would have been a clever fellow if he had been educated when young’, for with a large family of five or six, money spent on the education of one would deprive the others of food and clothing.

Holyoake therefore argues that the thoughtless working man supplies the weapons for his own defeat. No man is master of his fate so long as he keeps on multiplying ‘circumstances’ which control him at every turn. A large family, according to this freethought publisher, is the ever-present obstacle that stands in the way of education, reform, social comfort, and a thousand necessary and desirable changes.

If persons understood that it was possible to have early marriages, away from the notion that ‘he cannot marry until he has made a position in the world’, and had small families, a marked change, so Holyoake argues, would be visible in society within a few years.

What if in married life, the domestic affections may be more perfectly realised by a small family than a large one, he writes, where the truest love and the most generous consideration go hand in hand. Also, it should not be forgotten that the mother of numerous children risks her life eight or ten times, passing the best portion of her existence in continual suffering.

Holyoake concludes by saying that persons of a ‘philosophical’ turn of mind may control their own fate and maintain their independence and it is there that the balance of comfort lies.

Cami Garcia