Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

There is a positive drought sweeping over us, which threatens to create a bleak, desolate and fearful existence. We are blindly falling into oblivion and with each passing day there appears to be no arrest to our descent. News item after news item generates shudders and terrors as we stare fixedly into the stream of chaos, distress and horror with which we are seemingly presented.

The achievements of the 20th century that took so many great strides to overcome inhumanity are slowly showing signs of erosion. The abolition, by so many, of capital punishment is in great danger if one believes and becomes persuaded by ‘debating’ polls glibly erected to canvas a simple click of a button, which, if enough people press, starts to become a powerful political tool in the wrong hands. Can it be that we live in a society that can excavate and smash one of the foundations of a mature society by naively swaying the populace with fear? The focus of fear, of course, being that post 9/11 iconographic term coined by George W. Bush, ‘Terrorists’, which is now slowly but surely morphing into the term ‘migrants’. But really this is fear of the other.

The fostering and nurturing of fear, suspicion and hate is a real problem and left unchecked, it will cripple humanity through war and convince individuals to self-impose barriers to community that will escalate the loneliness and depression that swarms exponentially among us.

It’s time for a change and it’s time for us to realise what we mean to each other even if at first we don’t understand one another and can’t see why we each believe or do the things we do. The lessons learned in the twentieth century and the results achieved subsequently by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights have shown us the danger that lurks in each one of us and also the good that we can collectively attain, striving for global civilization. We must not go backwards, we must continue to strive, we must also realise the risks we face every day by lazy thinking that seeks to reduce questions of other people to problems that must be overcome. Each of us deserves consideration, thought and understanding. Each of us deserves to be treated ethically, because we are all people.

Hans-Georg Gadamer

Within his magnum opus, Truth and Method, Gadamer set down a re-interpretation of a neglected and overlooked school of thought: Hermeneutics, the study of understanding. For Gadamer, philosophy and hermeneutics needed to address what it is for us to live, breathe, and be among others in the world around us.

To begin with Gadamer tackled four particular areas: prejudices, horizons, conversation and the work of art. By taking each in turn, we shall see not only how Gadamer unveiled his philosophy, but also how he can open our eyes so that perhaps we may notice, acknowledge and welcome the ‘other’ into our lives and thoughts.

Prejudices

For Gadamer, the person gazing at the thing itself, for example, a book, undertakes a process whereby they “project a meaning for the text… because [they] read the text with particular expectations in regard to a certain meaning.” Such ‘expectations’ do not come from the thing that is gazed upon, instead the “person who is trying to understand is exposed to distraction from fore-meanings.” These ‘fore-meanings,’ according to Gadamer, come from our prejudices, our internal modes of orientation, with which we try to understand the world. They underpin our engagement with everything that we sense, and they help us to understand the new, the suspicious, the mundane, the beautiful, etc.

“Prejudices are not necessarily unjustified and erroneous, so that they inevitably distort the truth… They are simply the conditions whereby we experience something – whereby what we encounter says something to us.”

Gadamer’s main concern regarding prejudices, though, was that we need to be aware of their existence within us and that they exert influence whenever we try to understand something.

Horizons

Gadamer’s perspective was the realisation that the level of consciousness we have so far been able to attain is analogous to a personal horizon. Whereby we find ourselves, as he put it, with a “range of vision that includes everything that can be seen from a particular vantage point.” Which, because Gadamer was focussed upon hermeneutics – the study of understanding, translates into consciousness having a fixed point around which it perceives the world.

At this juncture, it is important to note that in order to have consciousness one needs to have a horizon. Without such a horizon one finds themselves somewhere between a goldfish and a sty-bound pig. As Gadamer conversely illustrated, “A person who has no horizon does not see far enough and hence over-values what is nearest to him”. Rounding it all out, the near-sighted person, if one follows Gadamer’s logic, has little or no consciousness.

However, we are limited by what we can see within our horizon and advancing beyond it requires a shift in consciousness. This should not present too drastic an obstacle though, because by the very fact of having the horizon – an important first step – we are also able to comprehend that there are sights beyond our current vision.

There is a second critical stage to Gadamer’s work on horizons and how we think, understand and engage with the world. In order that we do not objectify the other, or their claim, we must avoid trying to assimilate them into our horizon as it stands, but also we should not attribute an alternative horizon to them into which we transplant ourselves whilst ignoring our own horizon. Instead of objectifying them, as in the former, or indeed objectifying ourselves, as in the latter, we need to recognise the fluidity of ourselves with the other and attempt to achieve what Gadamer termed a “fusion of horizons.”

For Gadamer, the “fusion of horizons” required regulation, and this he saw as the task of a “historically effected consciousness.” In talking to Carsten Dutt, Gadamer said “we must take the encounter [potentially fusing horizons] seriously” because “one of the most essential experiences a human being can have is that another person comes to know him or her better.” Isn’t that what we all want – to be understood? To have someone that listens properly to the wit and wisdom we have to bestow whilst also appreciating the depths of our torment and the highs of our joyful responses to the world.

Conversation

Gadamer articulated three conditions regarding conversation. The first was that one must allow the subject matter of the conversation to dictate the flow of the conversation, and that one should not enter into a conversation with a pre-determined goal if one wants to have a genuine experience. The second was that one must remain open to what the other actually gives within the conversation, and hence respond to those opinions and not just what arises in one’s own thoughts. The final condition, for Gadamer, was that “every conversation presupposes a common language, or better, creates a common language.”

“Conversation is a process of coming to an understanding. Thus it belongs to every true conversation that each person opens himself to the other, truly accepts his point of view as valid and transposes himself into the other… Where a person is concerned with the other as [an] individuality – e.g., in a therapeutic conversation or the interrogation of a man accused of a crime – this is really not a situation in which two people are trying to come to an understanding.”

Understanding through conversation, therefore for Gadamer, requires that each person regard the other’s opinion and not just the other as an object. A stunningly obvious truth, but one that absolutely needs stating, in this current climate of fear, suspicion and hatred towards immigrants.

The necessary realisation being that we need to stop looking at, and start looking with, if we want any actual understanding to emerge, because understanding comes through participation not observation as far as Gadamer was concerned.

The Work of Art

“The work of art has its true being in the fact it becomes an experience that changes the person who experiences it. The ‘subject’ of the experience of art, that which remains and endures, is not the subjectivity of the person who experiences it but the work itself.”

Excusing the fact that the translation has managed to provide us with the word ‘experience’ four times in two sentences, there are three neat mini-revolutions contained within this terse prose: First, there is the explicit challenge to accepted models of understanding in both aesthetics and epistemology. In both disciplines, the standard criteria for the experiential subject is to be static and stable, and not as Gadamer proposed dynamic and changeable. Second, the statement regarding the work of art’s ‘true being,’ the attainment of which is predicated upon its ability to alter the spectator, acts to license the judgement of the work in a radical manner, in that any such judgment is determined by whether or not there is a perceivable effect upon the viewer. Finally, the third element, in contrast to the malleable spectator, sees the work itself remaining constant.

Perhaps, its as well now to make clear and bring completely in focus that whenever we describe the engagement with an ‘artwork’ or ‘work of art’ we are building a template for how we could engage with one another person. Make no mistake, all Gadamer’s work on aesthetics has an implicit ethical lesson. So, the person – migrant – is not like some alien from another universe into which we are magically transported for a time. Rather, we learn to understand ourselves in and through them.

Let’s look at some art to visualise Gadamer’s thoughts. In 1650, Velázquez painted his portrait of ‘Pope Innocent X’.

Ever since, the work has been revered by art connoisseurs, for example, Hippolyte Taine described it as “the masterpiece amongst all portraits.”

Three hundred years after Velázquez, Francis Bacon painted several variations on Velázquez’s original work and managed to create a total reformation and new icon in the history of art: ‘The Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X,’ affectionately known as the ‘Screaming Pope’.

There are many respected art critics and aestheticians that venerate Bacon’s work and consider it a triumph of genius. Robert Hughes said, “once you have seen two or three of Bacon’s screaming pope’s, you can’t get them out of your mind.” And this is it. This is Gadamer’s point. Some art “has its true being in the fact it becomes an experience that changes the person who experiences it.”

When one sees the ‘Screaming Pope’ for the first time one comes away changed. The experience of it alters our perception of what painting is. Somehow the work invades our mind, sets up shop, and makes us slightly different from who we were before. And this power, Gadamer understood, is the “true being” of art: the power to change “the person who experiences it.”

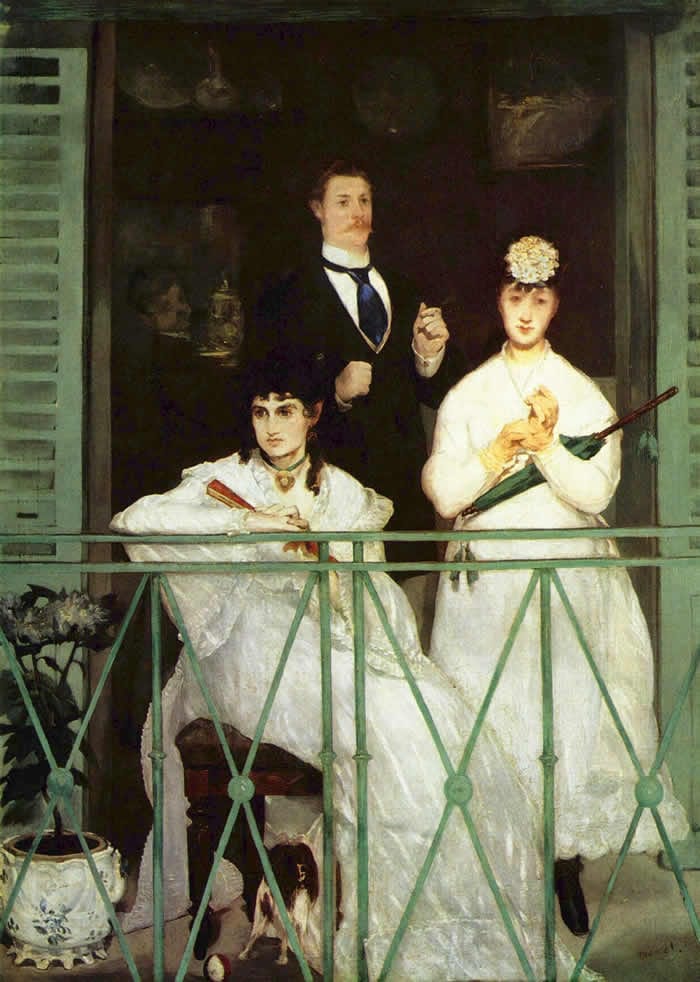

In 1868, Manet painted one of his iconographic scenes of the bourgeoisie at rest, ‘The Balcony’, containing friends and family as the main figures in an homage to Goya’s ‘The Majas at the Balcony’.

In 1950, a confident and self-assured Magritte painted ‘Perspective II. Manet’s Balcony’. The work is an exact reproduction of ‘The Balcony’, except that each of the figures is replaced, or encased, by a coffin shaped to match their posture as depicted by Manet. Here we see the same power to shock and disturb as we saw with Bacon’s ‘Screaming Pope’.

Viewing Magritte’s work alters one’s understanding of what a work of art can be and how we are to engage with it. Gadamer’s idea demands that we consider the spectator as a malleable figure. The work of art has its “true being” or, perhaps switching things around, the work can truly said to be art, if it changes the person who experiences it.

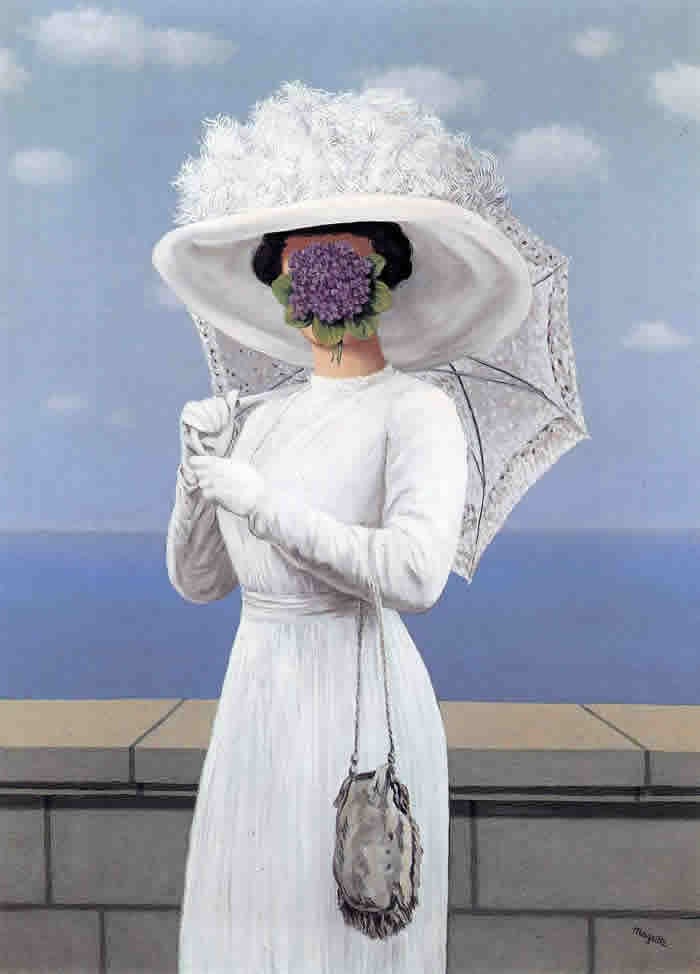

‘The Great War,’ for example, works to continually irritate us because the hydrangea is precisely in the way of where we want to look – the Edwardian lady’s face. We don’t cope too well when faces are covered up, obscured or removed entirely. Perhaps instinctively we are upset and disturbed by this. The face is after all where we direct our gaze when regarding each other and it is always our first port of call when examining portraits, the surroundings forever are secondary.

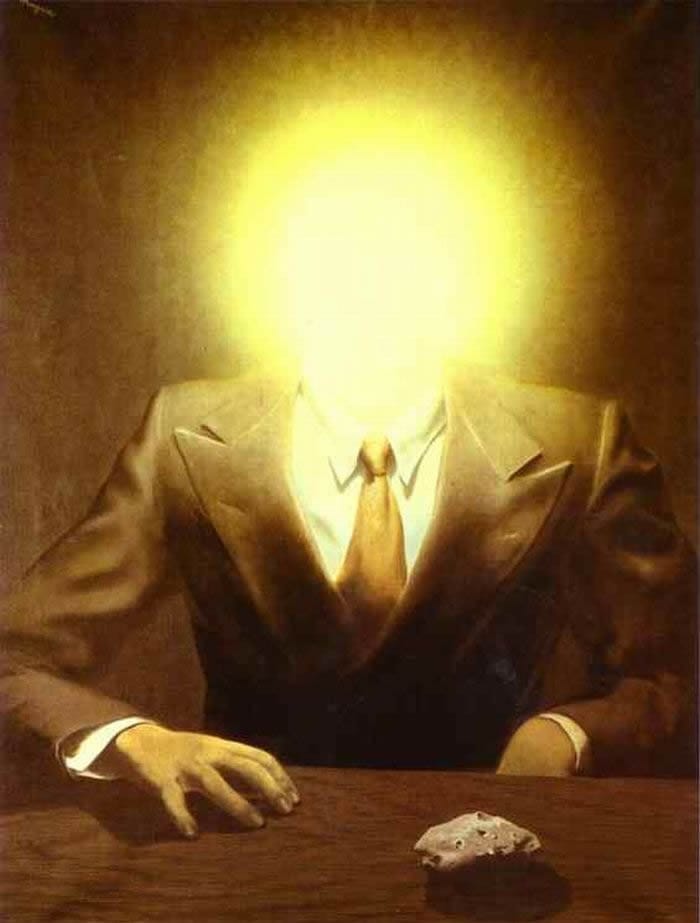

In ‘Not to be Reproduced’, Magritte plays further with this unsettling theme by giving the work the sub-title – ‘Portrait of Edward James’ – a device he repeats in ‘The Pleasure Principle.’

Both works deepen our sense of being unsettled because the solitary protagonist is actually named and the work presented as a ‘portrait’. Our expectations, therefore, become visually and textually distressed by Magritte courtesy of his painting and its title.

We need to acknowledge, though, that Magritte is a cypher for how we can relate to an artwork or an artist’s oeuvre. His work demonstrates the power that any art can have on us, in that we can be changed by it, if we let it. The question is can we let ourselves be affected by a work of art? Are we able to stand in front of something that we know could push us, change us, re-shape our boundaries, redefine our customs, and tinker with our deepest thoughts and emotions? Because what I hope to have shown with Magritte and Bacon can be found, and should be found, in the whole gamut of art. After all, one person’s Magritte is another person’s Miró, Picasso, Van Gogh, Michelangelo, Goya, or even Velázquez or Manet.

By examining Gadamer’s thoughts within the first half of Truth and Method, I think it is clear that a convincing case is starting to form concerning how we regard each other. And perhaps it is to ourselves that we should look first if we perceive that we have problems with migrants. We should reflect upon our own prejudices, the limits of our own horizons, our ability to enter into a real conversation and how a person, a migrant even, might be able to personally affect and change us for the better if we could only allow ourselves to regard them, in the same manner that Gadamer suggests we regard a work of art.

For a richer and more detailed account of the issues briefly mentioned in this article please refer to the posts in Jim Walsh’s blog, ‘An Ethical Thirst’.

![Perpective II- Manet-s-balcony-1950(1)[1]](https://www.conwayhall.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Perpective-II-Manet-s-balcony-195011.jpg)