Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

What does it mean ‘to know your own genome’?

Genetic knowledge has become much more easily available in recent years. We no longer receive information exclusively in the context of a conversation with our physician or genetic counsellor. Nowadays we can also obtain genomic information in the form of raw data, in the form of interactive web-based visualisations of genetic risk calculations, and in some cases, entirely without the involvement of clinical experts.

This opens up new options for test-takers: We can run our own analyses on our raw data, we can make sense of the data with the help of web-based tools, we can share our genetic and genomic information with others, or make it accessible for research. Not all forms of accessing genetic and genomic knowledge however are currently legally and practically possible for citizens. Should there be any limits on people’s right to access their own genetic information, or should we have a right to know our genome? Before I turn to this latter question, I will clarify what I mean by the genome, by the notion of knowing our genome, and by having a right to do so.

What is the genome?

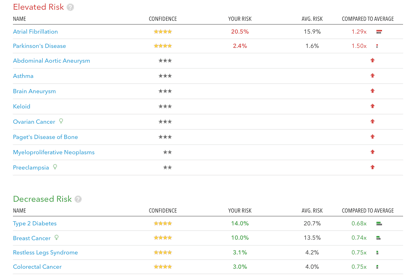

What is the genome? For the purpose of this argument, I consider any data representing any sequence of nucleotides in our genome – also if only within one specific gene or region – as ‘genomic information’. These could be print-outs from sequencing machines, for example, or interpreted information such as the disease risk calculations that online genetic testing services provide to their customers (see below illustration )

Illustration: Genetic risk information provided by a commercial genome testing company, 23andme.com, on the basis of the analysis of the author’s DNA. Such information is currently illegal to be given to patients in the US and other countries unless ordered and received by a licensed physician. In the UK, the company is allowed to disclose such information direct-to-consumer at present. Note: This genetic risk information is not predictive in the sense that it predicts people’s futures, but it is probabilistic.

What does it mean to ‘know’ your genome?

Sometimes when we speak of people ‘knowing’ their own genetic information, we refer not only to having access to this information, but also to storing and sharing it; with family members, for example, with medical reserachers, or even with the public as a whole. I discuss the question of storing and sharing one’s genome information in other publications (e.g. Prainsack 2014). Here I will focus on the question of access to information.

What does it mean to have a ‘right’ to know one’s genome?

The final question to explore before looking at arguments in favour of, or against, a right to know one’s genome is that of the meaning of ‘rights’ in this context. Should ‘rights’ be understood as negative rights, that is, as a person’s right not to be prevented from knowing her or his genome? Or should it be seen as positive right of a person to obtain knowledge of her or genome, if necessary at the cost of others?

The following section will discuss these latter questions in two scenarios, namely the in the context of the generation of genomic information in a clinical context, and outside of the clinic. (Please keep in mind that I am only discussing the person’s right to know her or his own genome, not on the claim of other people or parties – spouses, children, insurance companies, employers – to access another person’s genomic information, which would deserve a discussion in its own right.)

Arguments in favour of the right to know your genome

When bioethicist Ruth Chadwick addressed the question of a right to know our genome back in 1997, she saw such a right as relatively unproblematic. The principles of autonomy and self-determination, Chadwick argued, mandated that people should have the right to obtain information about their own genetic constitution (Chadwick 1997). In principle, this reasoning is still applicable today. In contrast to 1997, however, genetic data today are stored digitally, and data often move across domains or between different actors and institutions.

This means that our decision to access genomic information nowadays increases some risks, such as the risk of a breach of privacy and confidentiality (e.g. unauthorised access to data stored online), or creates new ones – e.g. the risk of causing distress to biological relatives if we decide to share our genome information with them or even to make it publicly available. Thus, the answer to our question of whether there should be a right to know one’s own genome should be influenced also by who would be affected by such a right. In this context is helpful to distinguish between two main settings within which genome analysis is carried out, namely the clinical and non-clinical settings.

Genome analysis in the clinic

The typical answer to the question of whether people should have a right to have their genomes analysed in a clinical context has so far been affirmative, and this right has been practiced as long as genetic analysis has existed (at least in wealthy countries where genetic testing has been used in the clinic). A requirement for patients to access genetic testing in the clinic is the presence of a medical indication, such as acute symptoms or other reasons to suspect genetic factors contributing to a particular disease or problem, a family history of diseases where genetic factors are known to play a significant role, or genetic testing in the reproductive context, such as pre-implantation genetic diagnosis, genetic carrier testing prior to procreation, etc.

Relevant caveats here are that not all of these scenarios are legal in all countries, and that access to clinical analysis of genes or genomes for particular purposes depends on the specific legal and regulatory provisions pertaining to cost reimbursement in a given country, region, or sometimes even institution. In sum, a right to know one’s genome – understood as being able to having it analysed in a clinical context – has been practiced for a long time, although it has not been universal and absolute.

In the clinical context, it is primarily the test-taker who is affected by the conseqeuences of her or his decision to undergo genetic testing, assuming that all clinical safeguards are in place, and that the information is safely stored in the clinical realm. In this scenario, also the risk of unauthorised access is low. If the test-taker has identical twins and multiples, however, or if the genetic or genomic analysis discloses information with significant clinical relavance also for other biological relatives, then the question arises whether these relatives should be able to partake in the testing decision in the first place.

I argue that in a scenario in which relatives of a person who wants to undergo clinical genetic testing want the person to refrain from doing so because they want to avoid receiving information that is also applicable to them (if only partially), then the interest of the first person in having her or his genome analysed outweights the interest of others in avoiding that they learn information against their will. An important reason for this is that if a person is referred to genetic testing in a clinical context, there is typically a health concern underlying this. Addressing this health concern must be considered more important than protecting other people from receiving unwanted information. Moreover, while for the person wanting to undergo genetic testing, there is no other way to know her genome than having it analysed, for those not wanting to receive certain kinds of information, there are ways to prevent this.

Even though these ways may not always be effective (e.g. if the test taker promises her twin or relative not to share the test results, but test result can be inferred from the test taker’s behaviour following the test), the interest of the person wanting to undergo clinical genetic testing to address a medically relevant question weighs more heavily than any interest of other parties. In sum, for genetic analysis in a clinical setting, I argue that there should indeed be a right to know one’s own genome. This corresponds with current practice in wealthy countries.

Genome analysis outside the clinic

A second instance of ‘knowing’ one’s genome is to have it analysed by another organisation or institution, typically a commercial provider and without the involvement of a clinician. This means that test-takers receive the analysed and interpereted data directly from the test-provider, often in the format of personalised disease risk calculations. Can we apply the same reasoning to genetic analysis in the clinical setting also also to this scenario?

In order to answer this question, we need to ask what the relevant difference between genetic testing within and outside of the clinic is, in terms of risks and benefits for the test-taker and any other potentially affected parties. The main difference is arguably the limited involvement of clinical experts in the testing process. As mentioned above, some countries allow for companies to disclose the interpreted results of genetic and genoic analysis direct-to-consumer, without any involvement of medical professionals on the customer’s side.

This means that test-takers rely on the information provided to them by the company or organisation carrying out the test. While many online genetics services place great emphasis of easy accessibility and comprehensiveness of information (i.e. they tell users how results are calculated, what markers are used for testing, and how genetic risks should be understood; see, for example, 23andme.com), most results of genetic tests are probabilistic.[2] Some authors are concerned that lay people struggle to understand probabilistic information without the help of a clinician (e.g. Howard & Borry 2012). If we accepted this assumption, then this would mean that both test-takers, and their biological relatives (if test-takers share test results with them) would be at greater riks if they received test-results from commercial providers than if they received it within a clinical setting. Moreover, commercial testing services often disclose information that is not clinically actionable (e.g. genetic risks for diseases for which no effective preventive measures or treatments are available), , or not even medically relevant; there is no consensus on whether access to this additional information is an advantage or an additional risk.

Also here, I argue that a person’s decision to do have her or his genome analysed outside of the clinic – irrespective of whether or not there is a medical question motivating this desire –is typically an expression of this person’s autonomy. From this perspective, the person should have a right to do so, unless there is a valid reason for (i) the need to protect the person from her- or himself, or (ii) the need to protect others from unwanted information. With respect to scenario (i), there is no compelling evidence that customers of commercial or other non-clinical genetic testing services are negatively affected by receiving test-results without the the involvement of a clinician (for an overview, see Saukko 2013).

Moreover, some authors, including myself, have argued that in order to understand why people take such tests, we need to extend our concept of utility from clinical utility in the strict sense of the word to personal and social utility (Vayena et al. 2012; Prainsack & Vayena 2013). Such personal or social utility can include that people benefit from learning about the genetic factors contributing to health and disease; that they can share potentially meaningful or relevant information with others, or ‘only’ that they find their engagement with online platforms proving such information entertaining. Such wider utility of genomic information has only begun to be explored. At this point, however, no compelling arguments exist to justify the need to protect people seeking to have their genome anlysed by a commercial provider from themselves because of the negative consequences that this knowledge would have for them. Any such negative consequences could very well be balanced by benefits. It is likely that the concrete balance will vary from person to person.

Another risk inherent in genetic testing outside the clinic comes from the fact that policies on data protection, privacy and data sharing outside the remit of clinical guidelines vary greatly. In the early days of online genome testing, concerns focused on databases in the commercial domain being hacked or leaked (e.g. Gurwitz & Bregman-Eschet 2009). Since then, our attention has shifted towards the business models of some of these services, which regularly include selling (anonymised) data to other commercial partners. Because not all test-takers read the small print of the terms of service, it can be assumed that many users ‘consent’ to their data being shared, and/or transferred to the ownership of the service, without their being aware of it. Is this, however, a sufficient reason to conclude that people wanting to undergo commercial testing need to be protected from themselves?

This would be a rather drastic step to take, considering how many other practices we engage in on a daily basis without being aware of the possible consequences. What needs to be emphasised, however, is the need to raise awareness of the possibility of such unintended consequences, and provide incentives to genetic testing providers to be proactive in communicating their data protection and data sharing policies to potential users. One such unintended consequence may be the fact that by allowing commercial genetic testing companies to use our data, we are inadvertently creating value for them (see also Parry 2013).

With regard to family members not wanting test-results to be shared with them, such concerns should be taken very seriously, because they are, in this case, often not outweighted by a medial reason for test-taker wanting to undergo testing. It would certainly be desirable for test-takers to be encouraged to discuss – wherever reasonable and meaningful – with biological relatives and other family members what unintended consequences their test could create, and how these could be avoided.

Based on the reasoning presented so far, our answer also to the question whether a person should have a right to access information on her or his own genome in a non-clinical setting – is affirmative. Again, the articulation of a person’s desire to do this would be seen as an expression of her autonomy, and any other persons’s interest in preventing the person from doing so, either out of commerical interest or a biological relative seeking to protect herself from receiving unwanted information in the process – weights less heavily than the test-takers interest in accessing her raw data (NB this applies to situations in which the analysis has already been carried out; the question whether or not a person should have her genome analysed in the first place is a different one, see above).

Should the right to know our genome be a positive right?

Now that we have established that overall, a right to ‘know’ one’s genome should exist, should we also claim that a person’s right to know her genome should be understood as a positive right, requiring that resources are made available for her to undergo testing if these are not covered by the person’s health insurance, and if she is not able to pay for it out-of-pocket? I argue that the presence of a clear medical indication should be the separation line here.

The analysis and interpretation, and, if applicable, the formulation of preventive or therapeutic strategies following from this, incurs considerable costs for society. In cases where there is an immediate medical reason, imposing these costs on healthcare systems seems justified; in other instances, although people should be free to obtain, store, and share data and information about their own genome, they should not be able to claim the costs for doing so from shared resources.

Conclusion

I have addressed here the question of whether or not there should be a right to know one’s own genome. I have argued that for this purpose, a broad definition of the term ‘genome’, namely one that includes representations of any or all parts of a person’s genome, would be the most fruitful. Furthermore, after clarifying that this text will focus on access to genetic and genomic information, rather than storing and sharing it, I distinguished between two main settings in which genetic or genomic analysis is carried out, namely within the clinic and outside.

For both scenarios I came to the conclusion that people should have a right to know their own genomes. At the same time, potential test takers should be encouraged by test providers to consider the unintended consequences that this could have for them, and for others. This should be done preferrably in dialoge with other potentially affected individuals (typically family members). Those analysing and processing genomic information – may they be in the clinic or outside – should actively encourage test takers to do this.

- Tagged:

- genomes