Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

Three themes, challenging entrenched views, recur in my work. One is that Mark is the earliest of the canonical gospels and that, while the others have additional material, these are dependent on it. This thesis, substantiated on many grounds including changes that could only have happened in going from Mark to the other gospels instead of vice versa, creates serious problems for fundamentalists.

There is crucially no description, in the earliest surviving manuscripts of Mark, of a resurrection or an ascension or indeed any post crucifixion appearances by Jesus. There are twelve further verses in other manuscripts, recognised by most scholars as additions, written at some time in the second century. What was available to the later gospel writers was a narrative that ended inconclusively and incompletely.

A young man dressed in white at the empty tomb tells the women that Jesus has gone on to Galilee. The women flee in fear and that is where the gospel ends. So you can see why believers might write reams disputing what is indicated by evidence,that the gospel narrative is based on Mark. If Mark is the source, then there is no Lord, no son of God, no infancy in Nazareth, no resurrection, no ascension, none of this in a more original narrative.

The second finding is that the narrative of the gospels is derived from existing Jewish stories which Christian writers used as their source. This represents a challenge to the misguided presentation of the first followers of Jesus as Christians whose witness was then recorded in the gospels. The reality is that the followers and family of Jesus were Jews, the stories were Jewish and the schismatic sect denoted as Christian arose some years later, outside of Palestine.

The third recurrent theme is that Christian editors did, over the course of several centuries, edit and rewrite the texts to fit with the Church’s emerging doctrines. These include the idea of Jesus as the son of God, the fiction of Simon Peter as the founder of the Church and the inflammatory, false presentation of the Jews, instead of the Romans, as Christ killers.

The Transfiguration

In The Lost Narrative of Jesus, I have examined a crucial piece of text that describes an incident in which Jesus climbs a mountain with three companions, is ‘transfigured’, so that his clothes and in some versions his face glow with light, meets Moses and Elijah and is marked out by the voice of God coming from a cloud. The story of the transfiguration is perplexing, in that it contains a lot of bizarre and apparently discordant details.

The immediate, miraculous elements can be explained as a Christian overlay, in which Jesus is given precedence over the long-dead figures of Moses, representing Jewish Law, and of Elijah, representing the prophets. The point being made is that the old order is over and that Jesus and Christianity now take priority, with God pronouncing, ‘This is my son, the beloved, listen him’. That is, listen to him, as opposed to the word of Moses and Elijah. What is interesting is that, when all the obviously miraculous elements are taken out, there remains a connected story, with a lot of detail, much of it rather strange. It begins abruptly with a reference to an unexplained time gap of six or eight days. Jesus then goes up a high mountain with Simon (nicknamed Peter) and the brothers James and John. They meet two people, who appear to have come from another direction, from or to the east. Jesus speaks with them. It is a secret meeting and the three disciples are sworn to secrecy.

It is late. Peter offers the two others their portable tents of wool or hide in which to sleep. This offer may well have been declined, as the visitors then depart or disappear. Jesus and his companions stay on, coming down the mountain the next day. There is apparently an odd discussion between them on the way down in relation to the scribes saying that ‘Elijah must come first’.

At the foot of the mountain, the group meet a large crowd that rushes forward in amazement to see Jesus. The other disciples are already waiting there and embroiled in an argument with some scribes. Jesus asks what the argument is about. At this point, there is a break. There is no answer to the question. A man in the crowd is given to reply to Jesus, but this bit of narrative lacks any reference to what Jesus may have said. It concerns instead a cure that the man wishes Jesus to perform on his son.

The Story was Interpolated

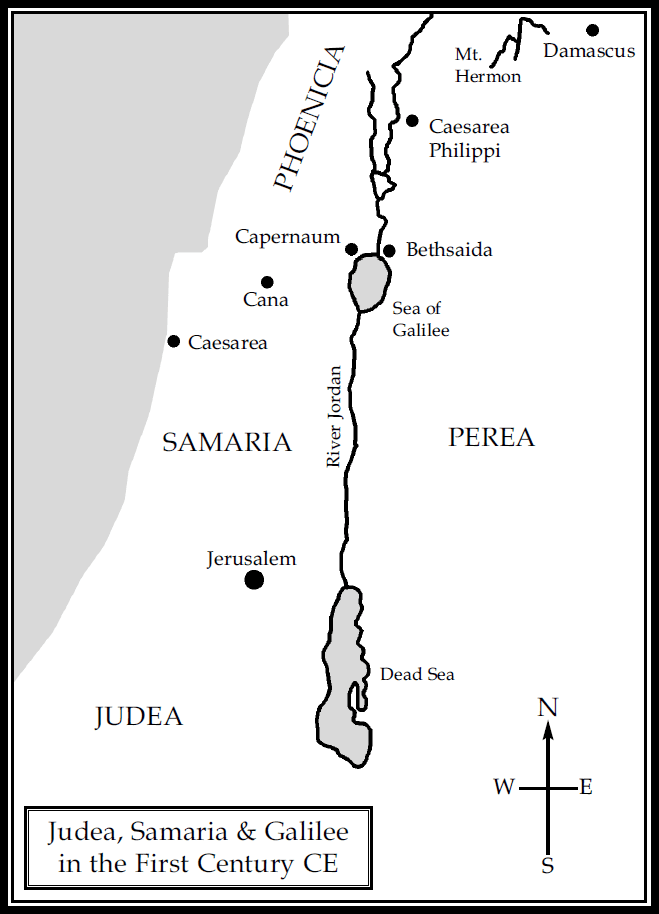

There is, however, a reference to Jesus addressing a crowd just before the transfiguration sequence, while going from Bethsaida beside the Sea of Galilee towards Caesarea Philippi at the foot of Mount Hermon. The man’s question about his son’s illness reads as a response to this. So the text runs on smoothly without the story of the transfiguration. As such, it is complete and coherent, describing a healing incident and without a diversion to a secret meeting on a mountain.

Together with dislocations at both the beginning and the end of the transfiguration story, this provides a classic indication that the passage has been interpolated. It has been taken from somewhere else. But where? A strong clue is provided by the break at the beginning where it is stated that ‘after six days’ (Matthew and Mark) or about ‘about eight days later’ (Luke), after departing Bethsaida, Jesus and his three companions arrived at villages near Caesarea Philippi. Now, these are situated just below the only high mountain in the region, Mount Hermon, standing at over 9,200 feet.

The journey would cover 24 miles, a distance that could have been accomplished in a day or two at most. This leaves, as something unexplained, the gap of either six or eight days. The one place where this does fit is at the end of Mark, where there are two references to Jesus going on to Galilee. Jesus tells his disciples this is where he will be going after he is ‘raised up’. Later, a young man dressed in white asks the women at the tomb to tell the others that Jesus is going on ahead of them to Galilee, where they would see him ‘just as he told you’.

The text in Greek is written literally as ‘tell the disciples of him and Peter that he goes before you to Galilee’. It is odd that Peter has been singled out; the women are instructed to tell the disciples and Peter, when Peter was one of the disciples. But KAI, often meaning ‘and’, is a conjunction used frequently in Mark with a wide range of meanings. It could well, in this instance have meant ‘with’ or ‘together with’, which does make more sense and does, as it happens, fit with the transfiguration sequence: ‘tell the disciples of him, with Peter he goes before you to Galilee’.

So, now we have a description and predictions towards the end of Mark that match the narrative. Moreover, the journey from Jerusalem to the villages of Caesarea Philippi is about 81 miles and, for someone recovering from an ordeal could, on foot or on the back of a mule, have taken six or eight days.

One test of how plausible this explanation may be is to see how well other details fit with it. The amazement of the crowd is one puzzling aspect. Jesus had been to a secret meeting with three companions, who had been sworn to secrecy. As they arrived back down from the mountain, the crowd on seeing him rush forward in amazement. There is nothing in the text to indicate what might have induced such a reaction. No time for Jesus to perform a miracle of some kind or an extraordinary act of healing: the crowd were amazed simply to see him.

This makes no sense, if this is where the text should properly be in Mark, as Jesus is depicted as wandering in his ministry (or campaigning) from place to place. But amazement would have been an entirely appropriate reaction in a continuation that provided a climax to the passion narrative. Jesus is here described as having been captured and crucified during Passover. This is the dismal news that would have been brought to Galilee by those returning from the festival in Jerusalem.

But after an interval, another subversive version began to circulate. This was that Jesus had survived the ordeal and, perhaps after a period of recuperation, was making or had made his way back. This story, incidentally, is consistent with features in the gospel accounts indicating that the crucifixion was an uncompleted execution. Most crucially, the blow to break the victim’s legs, the act required to cause death, is lacking. It is, we should remind ourselves, just a story – though one that is compelling in its construction. The small band of Jesus and his protectors would have avoided contact with Herodian sympathisers, Sadducee collaborators and certainly any Romans on their slow journey through Judea and Samaria.

But they could hardly have avoided any contact at all and the news of what may have happened spread like a ripple ahead of them. For this reason, a large crowd had gathered where Jesus was expected to be the day after his expedition to Mount Hermon. The rest of the disciples were there, having followed on, just as they had been instructed in the narrative of Mark. The crowd was quite justifiably amazed to see Jesus, having believed him to be dead.There were some scribes also present, not only doubting (until they saw it) that Jesus had survived but contesting the significance of his reappearance.

And on this really hinges the Jewish narrative, before it was dismembered and reassembled. There was at the time a strong belief that the Last Days, as predicted in Old Testament prophecy, were at hand. The gospel of Mark is constructed to demonstrate and validate this assumption. At the very outset, the prediction – not of Isaiah but of Malachi – is set out, that God would send Elijah again, as a messenger, before the ‘great and terrible Day of the Lord’. But that messenger, the ‘voice crying out in the wilderness’ (quoted from Isaiah), is then immediately linked with John the Baptist who is described as appearing in the wilderness.

So John is identified in spirit at least as Elijah, returned to deliver the news that the day of judgement is at hand. Good news, in that it was expected that Israel’s enemies would on this day be defeated and punished. So, how is this is connected with the story of Jesus? We do not have the topic of the argument described between the scribes and the disciples, at the foot of the mountain, because that is where the interpolated transfiguration narrative breaks off. But there is both a reasonable surmise and also a strong presumption. The surmise is that the scribes may have been contesting that Jesus had survived, until the moment that he reappeared. The presumption is that the scribes were also arguing, as Jewish scriptural experts, against the significance of any such reappearance.

Jesus’ apparently miraculous survival from crucifixion could not, they were contending, be the last great sign of the imminence of the Last Days, because that could not happen until Elijah had come again, as God according to Malachi had promised. As support for this interpretation, there is what would appear to be a crucial fragment of the conversation moved slightly back in sequence.Jesus asks the disciples what they were arguing about with the scribes. Presumably they tell him. And they ask – the piece of the dialogue that has been moved back to the point of the journey down the mountain – why the scribes say that Elijah had to come first (as we as readers also know, because the basis in prophecy is set out for us at the beginning of Mark). Jesus points out that Elijah had come, in the person of John the Baptist. Thus the prophecy was fulfilled and the sign given by Jesus’ reappearance, his triumph over adversity as God’s ‘suffering servant’, was valid. The Last Days truly were at hand.

This assumption of an imminent End Time was something held in common by Jews and early Christians early in the first century. It did not work out for Jews because, instead of God visiting vengeance on their enemies, the wicked triumphed, through the victory of the Romans and failure of the first Jewish uprising. The Jews were scattered and their temple destroyed. It has not happened for Christians, in their reworked version of the story, with a now-divine Jesus expected to appear with God to deliver judgement on the unrighteous.

Still imminent, it was claimed, since with God, in a new slant developed to deal with the failure so far of a second coming, ‘one day is as a thousand years’. If all the detail is taken together, it does fit well with the proposal that the transfiguration sequence, an interpolated piece, was in its origins the core of what had been lost from the ending of a Jewish narrative. It was folded in, maybe even before the ink was dry, to what became the gospel of Mark.

As I suggest the narrative up to verse 16, 8 indicates, the continuation of the story was that Jesus went to Galilee with Peter, while the bulk of the disciples followed on. The duration of the journey, the presence of a large crowd, its reaction to Jesus’ appearance, the disputation with the scribes and its outcome – all these points support the thesis that the transfiguration contains a much-modified ending of Mark. There is incidentally no other good candidate for a ‘high’ mountain described in the gospel, apart from Mount Hermon, and six to eight days walk or ride from Jerusalem. It is now and probably was then covered with snow for most of the year, providing enough reflected light to make your clothes or your face shine.

From the foothills, the ‘villages’ in the region of Caesarea Philippi, it would have taken the best part of a day to climb around 15 miles to somewhere near the summit and then hold a meeting. So taking tents might well have been a wise precaution. It avoided the risk of having to choose between staying out all night in the open, or descending the mountain in failing light. But what was the purpose of the exercise in any more original story, assuming that the supernatural encounters were superimposed? There is certainly enough connected detail to indicate a coherent account that involved a journey with a purpose and a meeting of some sort. In the three gospel versions, the meeting is with two men. In one of several non-canonical versions, the Akhmim fragment of the Apocalypse of Peter, the two men talking to Jesus are described as standing ‘toward the east’.

We are now in the realm of conjecture. But in any story that told of an ill-fated confrontation with the Romans, leading to Jesus’ desperate ordeal and narrow escape, the next step should surely have been a period of recuperation in some safe place. This, I accept, is not described in any surviving piece of text. The next logical move would then have been to get back to the relative safety of Jesus’ home territory, Galilee. This is what is presaged in Mark and, I have argued, is described in the now-misplaced transfiguration sequence.

Following this, Jesus might well have wanted a meeting with his supporters or backers. This is in part what the sequence was about. Jesus and the other Nazorean Jews did certainly have a basis for support among the Jewish community in the semi-autonomous Decapolis town of Damascus, to the east – just on the other side of Mount Hermon – and the likely place from which the other party would have come.

Damascus was in fact about to become an even safer haven, through its return from Roman control to the Nabatean kingdom under King Aretas. But it was not a place of absolute security, as a mixed community with conflicting loyalties and soon to be subject to forays from Herodians like Saul in pursuit of dissident, zealous Jews. So, if Damascus were the place from which the two other men came, there would have been a need for secrecy, in the interests of both sides. The obvious topic of conversation would have been what to do next.

And, for the Jesus of the story line, there were few options. As a man who had challenged the Roman, Jewish Sadducee and Herodian authorities, he would wherever he went have been the focus of attention and at risk of recapture. The only option in the story, and possibly in any historical reality, would have been some form of internal or external exile. There is, extraordinarily, in Luke a direct reference to this. Because this is the only reference and it is not in Mark, but in a later gospel, it must carry limited weight. But Luke describes what the two men on the mountain were talking about, Jesus’ exile (in Greek, EXOΔON) which ‘he was about to accomplish in Jerusalem’.

The conventional interpretation is that this is a reference to Jesus’ forthcoming passion.There are two objections to this. Firstly, the word EXOΔON is used frequently in the bible for physical exile and such things as the movement of goods and the setting of the sun, but never as a straightforward synonym or euphemism for death. That is except for one usage in 2 Peter, where the writer appears to be seeking to justify such an interpretation for the transfiguration .

The second objection is that I have established, on the evidence, that the transfiguration sequence in the source gospel Mark was in its origins the lost ending of the original Jewish narrative. So, at the point of the discussion, the crucifixion had in the story already happened. This is another reason for taking EXOΔON, for its customary and almost invariable meaning, as physical exile. This was, in the fact or fiction of the story, Jesus’ only option. Why Jerusalem? Well, this could have offered a safe exit, the means to merge seamlessly into one of the secretive and closed communities of zealous Jews within the city or its desert hinterland. I must stress that I have here simply teased out an underlying Jewish story. Working out what may have been the historical reality behind this will be a formidable task.

- Tagged:

- jesus

- new testament