Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

We are nearly a quarter of the way through 2018, and so far this year has been a great one for celebrating women composers of past and present. The combined momentum from the centenary of the Representation of the People Act and International Women’s Day seems to have inspired a particularly great number of concerts dedicated to highlighting the success of women musicians, and I have been lucky to attend many of them in London and Manchester. I am excited to announce that I will be adding to the mix with a concert at Conway Hall, based on the women musician’s of the society’s past. Plans are now well on the way for the 24th June, so get the date in your diaries! More information will be available soon.

Meanwhile, I have decided that this is a good opportunity to focus some of my blogs on the women composers who will be included in the June concert programme, with the aim of revealing their links to Conway Hall and thus the reason for their inclusion in the programme. There were many women who could have been chosen, but to narrow it down I’ve selected only British composers whose works were programmed in the first 1000 concerts, and were in some way a special influence on the nature of the concerts. This week, I am focusing on the remarkable Ethel Smyth (1858 – 1944).

Ethel Smyth

Although Smyth achieved notable success in her day and is still a relatively well-known composer, her work in respect of the South Place Sunday Popular Concerts is an area that has not yet been studied, and perhaps rightly so. Smyth’s music featured very little in the first forty years of South Place concerts, appearing on only three separate occasions. Most likely this is because the bulk of Smyth’s chamber music output was written early in her career (around the 1880’s), as opposed to her larger scale works that were mostly written post-1900, at a time when she was more widely known. However, it does not appear that the South Place Orchestra paid much attention to her music either.

The date of the first performance of Smyth’s music at South Place is certainly significant. In 1910, age 52, Smyth met Emmeline Pankhurst and quickly joined the WSPU. She soon became a prominent activist and was arrested in 1912 along with 147 other women for taking part in a mass riot in London. Smyth was jailed for throwing a rock through anti-suffragist Lewis Harcourt’s window. A famous account by Thomas Beecham describes the scene of Smyth conducting her anthem ‘The March of the Women’ (composed by Smyth in 1910) with a toothbrush, whilst a crowd of suffragettes in the Holloway Prison yard sang. Such bold behaviour is just characteristic of Smyth’s feisty attitude towards life, which certainly contributed towards her incredible success as a female composer around the turn of the century. 1910 was also the year that Smyth received her first honorary Doctorate of Music from Durham University, confirming that by this stage in her career she had been recognised as an important British composer. Nevertheless, Smyth still felt it was often a struggle to get her compositions performed and this is noticeable in her absence from the earlier South Place programmes.

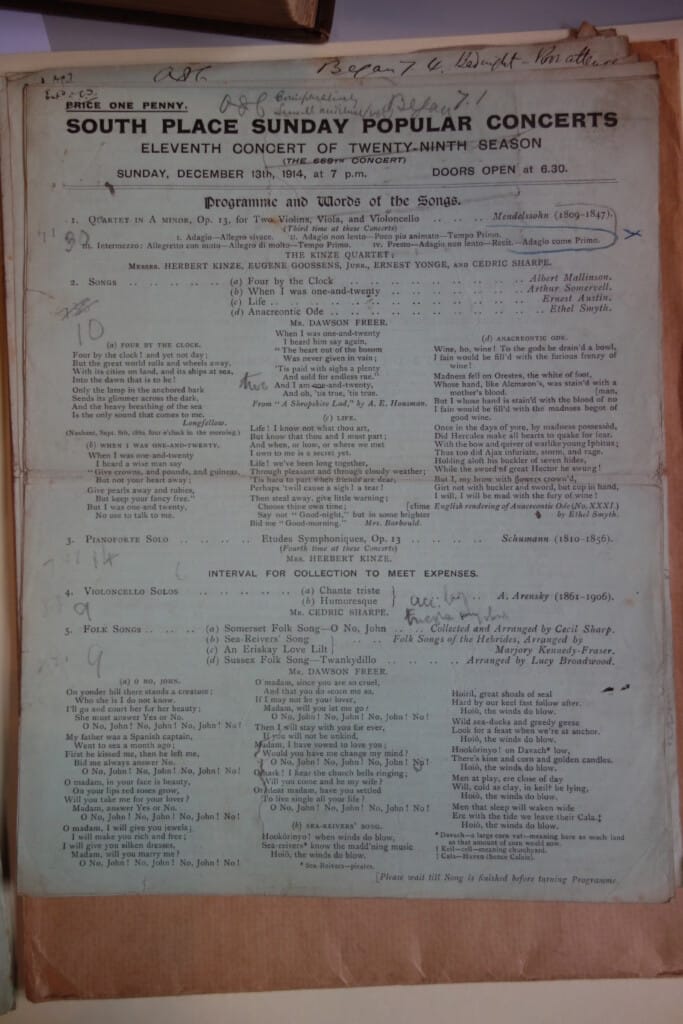

Yet, on November 20th 1910, Smyth’s name finally appears as the composer of a set of four songs: Odelette, The Dance, Chrysilla and Anacreontic Ode. This substantial collection of songs took up 25 minutes of the programme and was performed by a South Place Concert regular, Miss Grainger Kerr. It is very likely that Alfred J Clements and the other concert organisers would have been well aware of Smyth as a composer and it is possible that her recent militant action drew her closer to their attention. Paradoxically, the official stance of the Ethical Societies was to support the women’s suffrage movement, but believed it should be a peaceful fight and was against the militancy of women such as Pankhurst and Smyth. South Place, however, was regularly out of sync with the other Ethical Societies and many members had differing views. Clearly the concert committee did not see Smyth’s militancy as a problem. The fact that in 1910 Smyth announced her official break from music in order to fight for the vote suggests that the concert committee were supportive of her actions. This does not necessarily reflect the views of the rest of the Society, as the concert committee sometimes programmed religious music that would not have been in line with other members’ thinking. However, there were regular discussions and debates among many of the members about the relationship between music and ethics, suggesting that there would definitely have been some consideration over programming Smyth, a potentially controversial figure. South Place was renowned for its radical views and active involvement with moral and political issues of the day, and feminism and the vote was a regular hot topic, so the inclusion of Smyth in the Sunday Concerts appears to be the musicians’ way of contributing to that discussion.

-

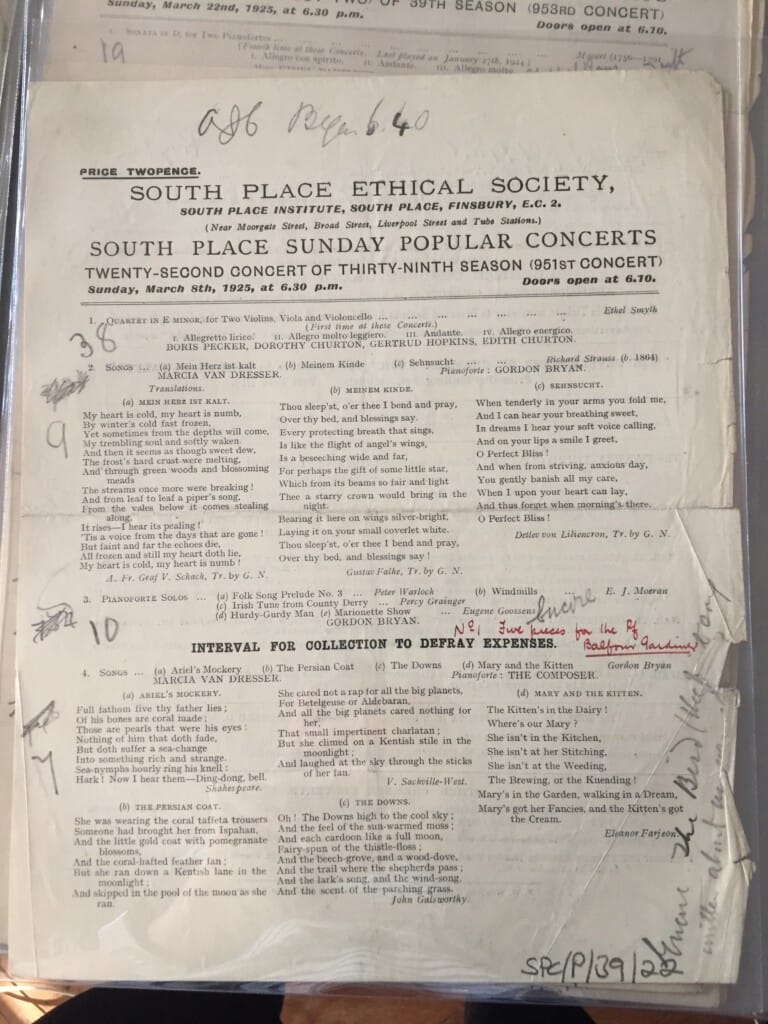

- Concert Programmes from 1887 – 1927 featuring Ethel Smyth

-

- Concert Programmes from 1887 – 1927 featuring Ethel Smyth

-

- Concert Programmes from 1887 – 1927 featuring Ethel Smyth

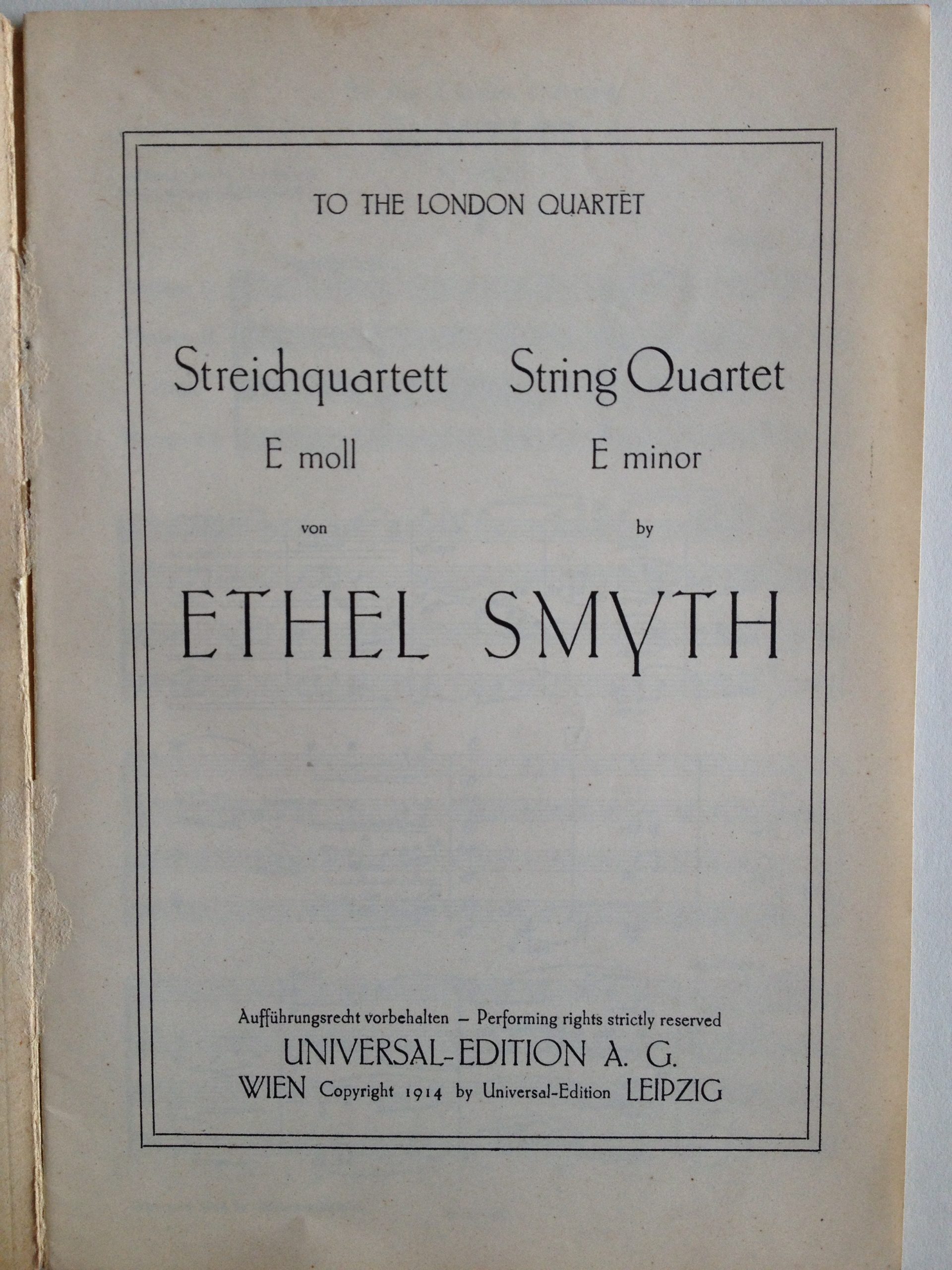

In December 1914, Mr Dawson Freer performed the playful Anacreontic Ode for a second time. He also performed three other songs by male British composers and a selection of British folk tunes – a seemingly patriotic selection during the early war years. It was not until 1925 that Smyth’s name reappeared in the programme. Despite the infrequency of programming her music, this was another substantial work. Smyth’s E minor string quartet is a forty-minute work comprised of four movements, each contrasting but filled with bold and energetic moments. Having started the work in 1902, Smyth abandoned it in favour of working on an opera, and didn’t complete the final two movements until ten years later. Harry Brewster, a man who she had a close relationship with for many years, passed away shortly before her return to the piece, and the solemnity of the Andante in particular seems to reflect her feelings of grief. The work has been analysed from a variety of perspectives: Elizabeth Wood claimed the work is a representation of the struggle for women’s rights, whereas Jennifer Gwynn Hughes understood it as Smyth’s discovery of her lesbian voice. A common thread is that the music somehow represents an exploration of Smyth’s identity and ability as a woman, which is particularly poignant as her first published string quartet, which for centuries had been well-established as a male genre due to large outputs of high standard quartets by infamous composers such as Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. Throughout her career, Ethel Smyth smashed through a number of glass ceilings facing women composers, particularly through her operatic work, and with wide success. George Bernard Shaw admitted in a letter: ‘It was your music that cured me forever of the old delusion that women could not do a man’s work in art and in all other things’. Her passionate string quartet is a great example of how her work challenged the expectations of women composers in the early 20th century.

If all goes to plan, this significant piece of music will make up the second half of the concert in June, as an example of some of the larger scale works written by women composers that arguably deserved more attention when they were composed in the early 20th century. Although South Place did not programme much of Smyth’s music, it’s important that works such as the quartet were programmed in distinguished chamber music concerts such as the ones held at South Place, and it will be a treat to hear the music performed in a setting with such a strong connection to the 1925 performance.

If all goes to plan, this significant piece of music will make up the second half of the concert in June, as an example of some of the larger scale works written by women composers that arguably deserved more attention when they were composed in the early 20th century. Although South Place did not programme much of Smyth’s music, it’s important that works such as the quartet were programmed in distinguished chamber music concerts such as the ones held at South Place, and it will be a treat to hear the music performed in a setting with such a strong connection to the 1925 performance.

I’ll be back soon with a new blog on more of the composers set to feature in the forthcoming concert. If you have any question or comments, please do not hesitate to get in touch. Email: Jessica.Beck@student.rncm.ac.uk