Estimated reading time: 13 minutes

by Jessica Beck

On Sunday 17 February I had the opportunity to give a pre-concert talk to a delightful audience at Conway Hall. For those who attended, this blog offers a reduced recap of my discussion, and thank you again for coming! If you couldn’t make it, here’s a little look at what you missed. The complexity of the impact of war means that the topics I cover here are by no means a complete overview of how the war affected the concerts, however they do offer new insights into how the war changed the lives of performers, programming and audiences in London, as well as how South Place adapted to ensure the concerts continued to run successfully.

Whilst World War Two affected South Place badly enough that the concerts were suspended for the first and only time in history, the Society managed to continue the concerts throughout the entire period of World War One. Other series were not so fortunate. For example, during the 1915-6 season, the Peoples Concert Society (who originally set up the concerts at South Place) had to dramatically decrease the number of their annual concerts down to sixteen. As the war went on, the call to arms affected the availability of musicians and their audience, and subsequently the PCS committee decided to cease operations until the war was over. In contrast, the concert series at South Place Chapel in some ways thrived during these challenging years. Money was always a struggle for the South Place concert committee, but in some ways this was less of a problem during the war, as occasionally money came from other sources who were keen to keep the arts going in London as a way to keep up morale and normality. For example, in 1915, the series was extended by five concerts, as the Committee for Music in War Time offered financial backing to support their efforts, promising that they would cover any debts incurred by these concerts.

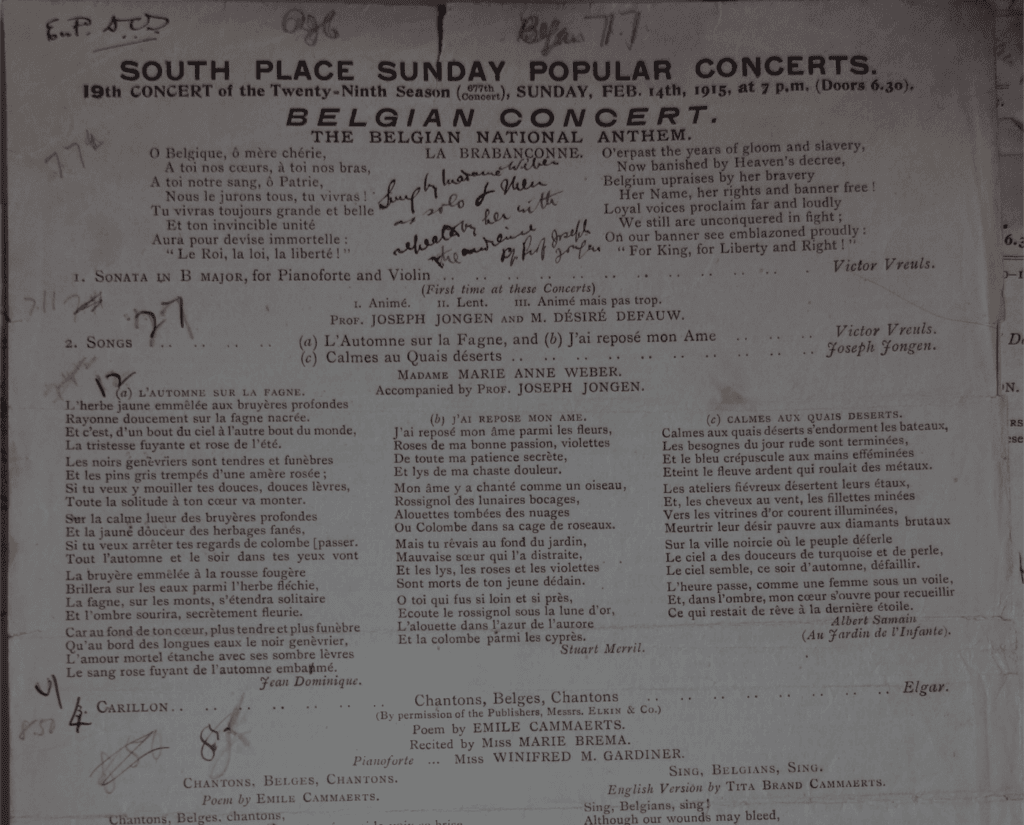

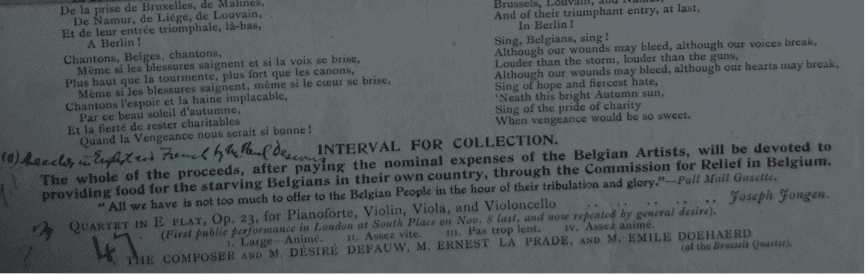

During this period there was a noticeable rise in composers programmed from allied countries, as well as special national concerts including those dedicated to Italian, Russian and French music. They also continued to host regular concerts promoting British music and performed numerous premieres. Most noticeable was the rise in Belgian music, largely influenced by the significant number of Belgian refugees who came to London during this period. In the 29thseason Clements organised two Belgian music concerts where he engaged Belgian musicians to play. An impressive £44/14/8 of profits were donated to the War Refugees’ Committee and the Commission for Relief in Belgium. It was during this time that Joseph Jongen became a regular performer at the concerts. Fundraising continued throughout the war for different causes. For example, in 1918 the String Quartet of the 31stMiddlesex Regiment gave a concert in aid of the British Red Cross, raising £15/1/6.

Initially the only trouble caused appears to have been the debate over whether to continue booking a German Bechstein piano for the following concerts. A letter was received from Steinway in an attempt to get the South Place committee to swap to their American brand, rather than continuing with the German firm. Concerned about the extra cost (typical of the committee), they decided to stick with the German Bechstein ‘subject to the omission of the name from the side of the instrument & from the programmes & any printed matter’, making any association to the German company invisible to the audience. There was also a discussion over whether songs should any longer be performed in German, but a Schubert concert and many subsequent occasions show that this idea was dismissed early on. For some time, after the fright of the Zeppelin raids, the concerts were also moved to an earlier time in the afternoon, but this was also reversed as soon as possible. The South Place Orchestral Society temporarily suspended their activities, but returned to giving regular performances in the 1920s.

Initially the only trouble caused appears to have been the debate over whether to continue booking a German Bechstein piano for the following concerts. A letter was received from Steinway in an attempt to get the South Place committee to swap to their American brand, rather than continuing with the German firm. Concerned about the extra cost (typical of the committee), they decided to stick with the German Bechstein ‘subject to the omission of the name from the side of the instrument & from the programmes & any printed matter’, making any association to the German company invisible to the audience. There was also a discussion over whether songs should any longer be performed in German, but a Schubert concert and many subsequent occasions show that this idea was dismissed early on. For some time, after the fright of the Zeppelin raids, the concerts were also moved to an earlier time in the afternoon, but this was also reversed as soon as possible. The South Place Orchestral Society temporarily suspended their activities, but returned to giving regular performances in the 1920s.

The archive at Conway Hall holds annual reports for every year of the concert series since it was taken over by the South Place committee in 1887. Having previously been very factual and unvarnished writing, during the war the reports became more descriptive, thus providing a unique insight into how London concerts were reacting to the war. At the outbreak of war, the committee had doubts over whether the concerts ‘should’ be continued, not whether they ‘could’, suggesting it was more of a moral quandary for them as to whether it was still suitable to host musical evenings during a time of international crisis. However, it was decided that the concerts could offer relief from the ‘strenuous duties of everyday life’ and provide support in their own way. This outlook continued throughout the war, although it became tougher every year. The second year saw a drop in audience numbers and greater difficulty hiring performers. In the annual report of the third season of the war years, the writer reflected on the changes that had occurred since the war, noting the toll it had taken on both performers and audience:

Gone are many familiar faces, but fresh ones have replaced them. Somehow folk from all classes of society have found their way to this home of the sublime art, situated in one of the busiest parts of the city, where they find in music a solace, one might almost say a drug, which for a few brief hours, will lull them into forgetfulness of this horrible world war. Upstairs in the gallery the pale-faced tailor from the East End, who works all the week in a stuffy little room somewhere in Whitechapel, sits next to a couple of bronzed Colonial fighters who are on short leave from a front line trench somewhere in France. Nurses and munition workers, red-tabbed Staff Officers and able-bodied seamen, and just ordinary civilians, sit side by side.

This is one of the most descriptive passages in any of the annual reports, which are usually focused on recounting the highlights of the season. The war years clearly shifted the perspective of the committee and forced them to analyse the influence of the concerts on a broader scale, with a much deeper consideration for the social impact of the concerts over the purely musical and educational benefits that they provided. Descriptions of their audience members are a rare feature in the reports. Whether their accounts factually correct or not, the reports reveal the perspective the committee had of the concerts during the war. References to the different roles that people had during the war – from soldier to civilian – give a sense of the audience being a place of equality and solidarity. The emphasis on distinctions of class and nationality suggests that the committee saw the communal activity of listening to music as a way of connecting people from different walks of life during a divisive time, supported by their efforts to be musically inclusive.

The report from 1918 retained a similar tone. There is a note of the rise in khaki among the audience and now on the platform, and a note is made of the incongruity of a man dressed in his war uniform playing sweet music – ‘surely the most peaceful of all the Arts’. The audience are also described as being ‘as cosmopolitan as ever’ yet bonded by the love of ‘good’ music. Such statements about the peaceful and good nature of music implies that despite the intense moral questions that must have been triggered by the war, there was still a sense of chamber music having intrinsic elevating and moral value.

Letters sent to the concert society during these years also give an emotional perspective on the place of the concerts during the war. One letter from a woman whose husband was a prisoner at war in Germany said that he would like to known what was ‘happening’ at South Place. Another was sent to say thank you to the Society for ‘many delightful evenings of sound and sweet airs’. A letter from a woman whose husband was seriously ill reads:

… with what joy he used to look forward to your concerts, and how he enjoyed them, he used to say they made life worth living, and I don’t think he has missed one of them. I hope you will excuse me for writing to you, but I felt I must, he always used to speak so kindly about you that you seem a friend of his.

It must be a rare thing for a concert promoter to receive such a touching letter that really demonstrates the role the concerts played in the lives of its audience members. Moreover, the letter indicates that at times of sadness, the concerts may have held a further purpose of comfort to friends and relatives of those who attended regularly, through the strong bonds that were created in that setting.

It is during the later years of the war that the subject of men and women musicians is raised for the first time in a way that distinguishes them from each other. As may be expected, the number of women involved in the concerts rose significantly during the war. There were more women performing regularly and there was a dramatic increase in the number of women on the committee, which was sustained in later years. In one of the concert reports, the author notes that the war has made it increasingly difficult to secure the services of male executants and vocalists, and the fact that the committee had been able to maintain the customary proportion was a valuable testimony to the concerts.

This statement is not quite true. During this season, there was roughly an equal split between male and female performers and vocalists, but this was absolutely not always the case. In most previous years, although there was a roughly equal balance between male and female vocalists, there was always a substantially higher proportion of male instrumentalists. So although South Place gave opportunities to women that may not have been as easy to acquire elsewhere, this was clearly not done without maintaining a certain proportion of male performers. From a more positive point of view, it suggests that the committee were aware of the gender balance presented at their concerts, and the fact that this was higher than in many other venues shows an awareness of the inclusion of women musicians that was not simply a by-product of the high proportion of women in the Ethical Society, or the fact that they were more likely to perform for free.

On describing the occasion of the 750thconcert that took place on 6 January 1918, the annual report stated: ‘Our lady friends have acquitted themselves with their wonted efficiency, and rendered splendid service throughout the season. Among these may be specially mentioned Miss Jessie Grimson, Mrs Ethel Hobday, Miss Myra Hess and the Misses Bentwich…’. This is followed by an appreciation of the talents displayed by the ‘lady vocalists’. It was fairly common in the annual reports for the ‘ladies’ to be commented on separately from the men, as a sort of sub-category. This did not usually include all of the women, just those who they clearly felt deserved a special mention but had not already been written about in detail. It is sometimes written as if some women with an especially high ability or reputation somehow superseded the category of ‘the ladies’. Although this does not appear to be intentionally dismissive or discriminatory, it does present the women as an ‘other’ at a time when women were equally as present as men.

Generally at South Place, the distinction made between the male and female musicians was in many ways overlooked. However, in the absence of greater numbers of men involved in the concerts during the context of war, South Place occasionally let more misogynistic attitudes slip through in places that had not previously been apparent. In a lengthy introduction to the Opus 1 concert that took place on 4 November 1917, ‘W.G’ intended to arouse interest within the audience in the early works of great composers. Given that my research on the whole argues that the South Place concerts were among the more successful concerts in London with regards to championing women composers, his words are troublesome:

There are few pages in a biography more fascinating than those which tell of the early days of a great man. The supreme interest of tracing the advent, the growth and the flowering of his special gift appeals to all in whom the love of art is found… One would like to think that the genius is a modest man. The real genius is and must be so; modesty, humility, eagerness to learn and power to endure are essentials of his nature.

The concert, performed in part by Jessie Grimson and Amy Grimson, predictably only featured works by male composers. Diversity was created in the concert through the disparity between the eminence of the composers (the first work in the concert was by Beethoven, and the last by James Friskin). The focus on ‘great men’ in the programme notes and the musical content seems to be somewhat compensating for the tragedies occurring around the globe, particularly to men at the front line, and simultaneously upholding the narrative of the male hero that was permeating war propaganda at the time. Whether it was purposeful, or accidental neglect, women are completely dismissed in this programme as potential ‘great’ composers, or indeed, ‘geniuses’. Whilst this concert and the message it portrayed should not be overlooked, it is a rare example of such blatant patriarchal language in the South Place concert programmes or even their more private administrative writing.

Contrastingly, in 1915 a special concert of women composers was organised in acknowledgement of the important work that women were contributing during this difficult time. Ironically, after this concert there was a considerable drop in the number of women composers that featured in the South Place concerts for many years. However, this concert features many of the composers and significant performers who had an influential role at the South Place concerts up to this point.

The same year as this concert, Rebecca Clarke, now best known for her viola compositions, joined the group of women who performed at the South Place concerts for the first time during world war one. At a later concert she returned to play alongside Marcel Laoureux, a pianist to the Belgian Court, and MM. Desire Defauw, a Belgian violinist and conductor. The singer in the concert was M. A. Coryn, director of the Royal Opera, Antwerp. Whilst this was not another concert raising money to support refugees, it was clearly an effort to show support to Belgium during the war.

Subsequently, songs she had written were performed several times at South Place, and the Bentwich sisters performed the ‘Lullaby’ from Clarke’s Duet for Strings. Clarke also continued to perform at the concerts sporadically throughout the 20s and 30s. It seems that like many other women musicians at South Place, Clarke’s long association and recurrent performances led directly to increased exposure of her own works at the concerts. In this sense, the increased vacancies for women during world war one were incremental to her later success at this venue.

Outside of South Place, Clarke performed with other South Place women, including Myra Hess, Marjorie Hayward and May Mukle, hinting that the close networking apparent among the South Place musicians also played a role in her career. However, before Clarke first performed at South Place she was already a successful musician, notably having been selected as one of the first women to play in Henry Wood’s Queen’s Hall Orchestra in 1912, along with Jessie Grimson.

Outside of South Place, Clarke performed with other South Place women, including Myra Hess, Marjorie Hayward and May Mukle, hinting that the close networking apparent among the South Place musicians also played a role in her career. However, before Clarke first performed at South Place she was already a successful musician, notably having been selected as one of the first women to play in Henry Wood’s Queen’s Hall Orchestra in 1912, along with Jessie Grimson.

Jessie Grimson was a notable performer at South Place long before the war. She first appeared with her family ensemble in the 1890s, which consisted of six of her siblings and their father. The group appeared at the concerts regularly. Soon, Grimson set up her own quartet, leading three men (including the now well-known composer Frank Bridge), an unusual sight for audiences at the time!

The war caused significant changes in Grimson’s personal life and her role at the concerts. The first tragedy was the loss of her husband and member of her quartet, Edward Mason, who was killed at the front on 9 May 1915, near Fromelles (France). His death was reported in the concert committee’s annual report, where he was described as an excellent cellist and choral conductor. The press noted him as ‘the first well known London musician to fall in the war’. In 1917, Jessie’s brother Harold was also severely injured in the battle of Cambrai, which ended his music career. The British Army Service Records stated that Jessie Grimson never recovered from her losses and gave up her performing career in 1927, however the South Place archive shows a different story. Even during the war, whilst presumably grieving from the loss of her husband, she continued to perform at South Place.

It is true that in 1927 Jessie Grimson did not play at the South Place concerts for the first time in 30 years, an absence which was noted by the South Place committee in their reports. Nevertheless, she returned the following year and continued to perform with a variety of musicians, usually under the name of the Jessie Grimson String Quartet, throughout the rest of the 20s and the 30s. It was during the war period that she started to include more women in her ensemble, who she continued to perform with in later years. The change in ensemble members and the context of the war clearly had an effect on Grimson’s choice of programming, which became much more traditional than it had previously been known for. There were less performances of contemporary compositions and more emphasis on Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, with a continued spattering of British music. Perhaps these more conventional choices were felt to be more appropriate for an audience looking for safety and escape during troublesome times in the capital.