Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

by Dr Jim Walsh, CEO of Conway Hall

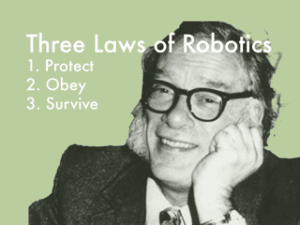

In 1942 Isaac Asimov wrote a short story called Runaround in which he set out his now famous Three Laws of Robotics:

A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Over eighty years later these three ‘laws’ are finding new audiences within emergent Artificial Intelligence discussions that vie to be top of the heap of things-we-should-be-really-worried-about. Climate change, war, pandemics, cost of living, political integrity (or not) now come along with a new friend into our lives – A.I. and concern about whether we should, or shouldn’t, experiment and develop it.

Over eighty years later these three ‘laws’ are finding new audiences within emergent Artificial Intelligence discussions that vie to be top of the heap of things-we-should-be-really-worried-about. Climate change, war, pandemics, cost of living, political integrity (or not) now come along with a new friend into our lives – A.I. and concern about whether we should, or shouldn’t, experiment and develop it.

As they go, Asimov’s three laws are pretty good for getting to some of the nub of the matter. In fact, most attempts to improve upon them feel like tweaking at best and knowing mockery at worst. What has rarely happened though is a complete overhaul or rebuild. Their simplicity seems to withstand tinkering, meddling, or blowing up.

An interesting line of thought, of course, occurs when one considers that all forms of AI are essentially built by humans and that they follow the programming set by such humans. Essentially, there is quite a lot of ‘human’ built into any piece of AI and, contrary to where you might believe I’m going with this line of thought, that isn’t necessarily a good thing. The ‘human’ input might be flawed, as so much of human existence has proven to be. So, are we able to trust the builders and programmers of our wonderful life-enhancing gadgets and devices that seem to become more powerful by the hour? Maybe a human might inadvertently skip part of the ‘Asimov Programming’ or load humorous but potentially deadly spark guns in place of the screwdriver function?

My personal fear is that a human might programme a ‘Whim Capacitor’ where the device exerts some form of free will or exhibits the AI equivalent of “I’m having a bad day” with accompanying acting out. It is also not beyond the realms of plausibility that any advanced thinking thing might rather swiftly conclude that humans are little more than basic parasites upon their given host, the planet, and that logically it makes sense if we were to be eradicated. Possibly, though, I have just given the elevator pitch of a thousand budding film directors.

My personal fear is that a human might programme a ‘Whim Capacitor’ where the device exerts some form of free will or exhibits the AI equivalent of “I’m having a bad day” with accompanying acting out. It is also not beyond the realms of plausibility that any advanced thinking thing might rather swiftly conclude that humans are little more than basic parasites upon their given host, the planet, and that logically it makes sense if we were to be eradicated. Possibly, though, I have just given the elevator pitch of a thousand budding film directors.

Of far more interest to me is the line of thought that peers into the relational dynamic between a human and an advanced artificial intelligence because this is where I think there is some philosophy juice to squeeze.

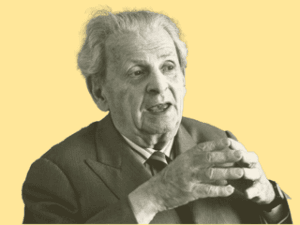

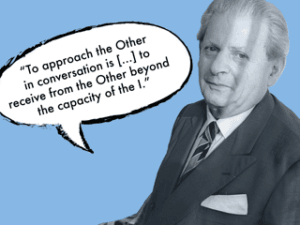

Emmanuel Levinas, writing in the 1940s to 1990s, was deeply concerned with how humans treat each other. He was so concerned that he decided to dedicate his career to writing and thinking about ethics as first philosophy (as he called it).

One of his key concerns was a tendency he observed in Western thinking to ‘totalise’ everything under the gaze of the observer. By which he meant that each of us, as a human subject, seem to be driven, especially in the Western model of rationality, by a compulsion to understand everything we see and place it within our individual systems of thinking that we have so far arrived at.

In the main, he knew that this was a good thing, because we could develop and evolve to understand our planet and our place within its glorious splendour (my embellishments not his!).

The problem, for Levinas, was that this totalising gaze falls equally onto things as it does onto humans. The light of rationality leaves no place for shadows when understanding is the goal. Essentially, my totalising gaze looks to bring you into my understanding, and I look at you in the same way as I might look at a chair or a cup of coffee. My goal is simply to understand. My goal is not – and this is the point – to respect, be kind, or act ethically towards you. Nor is my goal to allow you your autonomy. The totalising gaze is the cold hard stare of dehumanisation.

The problem, for Levinas, was that this totalising gaze falls equally onto things as it does onto humans. The light of rationality leaves no place for shadows when understanding is the goal. Essentially, my totalising gaze looks to bring you into my understanding, and I look at you in the same way as I might look at a chair or a cup of coffee. My goal is simply to understand. My goal is not – and this is the point – to respect, be kind, or act ethically towards you. Nor is my goal to allow you your autonomy. The totalising gaze is the cold hard stare of dehumanisation.

For Levinas, we had to move beyond the totalising gaze to a position of ethics when being with each other. Ethics and a deep sense of responsibility for the other were the Alpha to Omega of our interactions with each other. The totalising gaze simply had no place in the dynamic of human-to-human relations for Levinas.

This leads me to my AI point: will AI, as it evolves, regard us with a totalising gaze or one that looks beyond our physical features and make allowances for the myriad diversity and autonomy that we possess?

Because no matter how much we might programme AI to fit a model of perfect integration with us, we humans are never going to become uniform nor always act in expected or manufactured manners. Our individual autonomy, and deep need to be respected for who we are (not just an as example of a human being), mean that we will not tolerate being dehumanised by any one’s, or any thing’s, totalising gaze. This means that it’s time to start thinking about how we are with each other – never let go of that. But, also, can AI be hard-wired with a “Levinasian Humanizer” that ensures we go beyond questions of harming, obeying and protecting into much needed arenas of respect, kindness, and compassion? Just as we need to be more ethical towards each other so too, do the products of our hands, minds and programming.

Because no matter how much we might programme AI to fit a model of perfect integration with us, we humans are never going to become uniform nor always act in expected or manufactured manners. Our individual autonomy, and deep need to be respected for who we are (not just an as example of a human being), mean that we will not tolerate being dehumanised by any one’s, or any thing’s, totalising gaze. This means that it’s time to start thinking about how we are with each other – never let go of that. But, also, can AI be hard-wired with a “Levinasian Humanizer” that ensures we go beyond questions of harming, obeying and protecting into much needed arenas of respect, kindness, and compassion? Just as we need to be more ethical towards each other so too, do the products of our hands, minds and programming.